The Pencil Tree

Once upon a borrowed time in the quiet Kandhava Forest by the Yamuna River, there lived a tree who was known by all the other trees as The Pencil Tree.

Now – this was a borrowed time, a time borrowed well before History began. This was even before Herodutus. Long before Julius Caesar and Cornelius Tacitus set their heart upon the Rhineland, and long before Marcus Tullius Cicero, and even before the time of his role models in the Roman Republic. This was before Pompey and Cato the Younger and Pliny the Elder.

Conifer trees having a coniference

However, there were Elder Trees in the Kandhava Forest at that time. And these Elder Trees, like clusters of trees in forests all over the earth, heldconferences during the planting seasons.

All trees held conferences except of course for the conifer trees, which held coniferences.

In those days, when forests and animals and birds lived upon borrowed time, there was a plentitude of specie. Of the dodo and the duckbilled, of the Peregrine falcon and Pyriglena atra, of the Indian pangolin and the Indian tiger.

The Elder Trees’ Conference

It started to get very warm and very noisy in the quiet Kandhava Forest and the Elder Trees hastily called for an emergency conference. As always, everyone was there exactly on time. The Elder Trees clustered around The Pencil Tree and told the news that they had just heard:

The Lord Vishnu, who had appeared as a dwarf and conquered the giant Bali and reclaimed the Universe in a previous incarnation, was now reincarnated in another life as the Lord Krishna. And Krishna, together with prince Arjuna, had been bathing some miles away from the cluster of trees around The Pencil Tree, upon the banks of the Yamuna River near Kandhava Forest.

The Woodsman and the Ghee and the Bow and the Discus

As they finished bathing and strolled along the riverbank, Krishna and Arjuna encountered a weak, thin, frail, hungry-looking woodsman, dressed in tattered rags, who claimed he had been eating ghee to quench his hunger. Arjuna, ever the compassionate prince, asked the woodsman to name whatever food he desired and Arjuna would provide it for him. The woodsman held out his hand in which there was a ball of fire. He then said he was so hungry that he desired to devour “The Forest of Kandhava”! He wanted to consume the whole forest.

This was no woodsman. This was a trickster. This was Agni, the Lord of Fire!

Arjuna had given his word, and he knew that he and Kirshna would have to honor this promise. Agni then gifted Krishna with a bow named Gandiva, which came with two quivers that never ran out of arrows and had bright blazing balls of fire on the arrowhead tips.

It was now time for the History of Man to begin.

Krishna would use his bow, Gandiva, while Arjuna gathered his deadly discus, Sudarsana, and together they resolved to kill all the wildlife in the Kandhava Forest, all the animals and all the birds; while Agni himself, the Lord of Fire, resolved to burn the entire forest down. Agni began to burn down all the trees and all the vegetation of Kandhava Forest to quench his appetite.

What then must we do?

No wonder it was so warm in the forest as the Elder Trees held their conference. Just a few miles away, the raging fire that Agni had ignited was burning voraciously. Krishna with his bowGandiva, and his friend Arjuna with his lethal discus Sudarsana, were riding upon a chariot of solid gold and carried by a pair of thoroughbred horses. They burned everything they saw.

“What then must we do?”

This was the question one of the Elder Trees asked while the ominous fire blazed in the near distance and the birds and animals, the peacock and the tiger, scurried swiftly, trying to evade fireball arrows from Gandiva, Krishna’s bow. Rare birds and noble animals were felled that day.

“If we stay where we are,” said The Pencil Tree, “ we shall be consumed by the fire and we shall be cremated alive. Better that we call a real woodsman – not that impostor Agni – and ask the woodsman to chop us into small pieces of wood and bury us in a clay-covered grave.”

The Elder Trees had always respected their young friend, The Pencil Tree, and so they summoned the woodsman and The Pencil Tree explained his plan to the woodsman:

The woodsman would chop them down and ask his men to carry the chopped trees to the giant village kiln, where sweetened wheat cakes and paratha were usually baked. The woodsman was then instructed to collect all the ghee in the village and paint and soak the wood of the chopped trees in ghee to preserve their vitality. Finally, the wood must be covered with a thick clay covering to protect it from the encroaching fire, thus preventing a premature cremation.

The secret of all these events would be kept within the woodsman’s family for generations– for centuries – until it was finally right to open the clay covering and retrieve the hidden wood.

Borrowdale, The Lake District in Cumbria, England, around 1550

Sheep farmer Jethro, had a lot of sheep.

Farmer Jethro’s neighbors were also sheep farmers. So this presented them all with a complication: how do they identify one flock of sheep from another flock when one of the sheepescapes the flock? It was a real predicament. Nobody knew what to do about it.

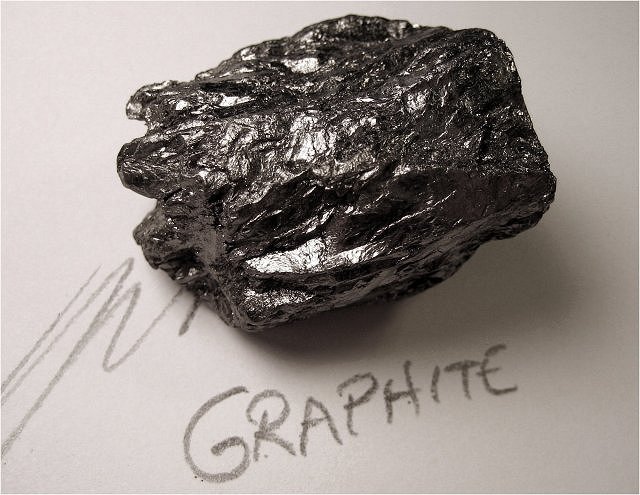

Now one day, the farmer stumbled upon a giant deposit of graphite on the Seathwaite hamlet. Jethro quickly figured out that the chunks of graphite could be used to mark his sheep.

He also realized he could chop the chunks of graphite into little sticks so that it was easier to transport the graphite while he was herding sheep. He could put the graphite in his pocket.

The Pencil was Born

Next, someone figured out that the brittle graphite could be prevented from snapping and splintering if it was encased in a piece of wood upon either side, each wood piece then glued together to strengthen the protective layer. Wood and graphite belonged together now!

Next, someone figured out that the brittle graphite could be prevented from snapping and splintering if it was encased in a piece of wood upon either side, each wood piece then glued together to strengthen the protective layer. Wood and graphite belonged together now!

The pencil was born.

The oldest pencil: graphite with a piece of wood glued on to either side

Kandhava Forest, generations and centuries after Agni’s fire

News of the birth of the pencil traveled slowly in those days, but it reached the generational great grandson of the original woodsman who had chopped up and hidden The Pencil Tree. It was time to smash open the thick clay covering and announce the birth of the pencil.

After the woodsman cracked open the clay covering with the heavy blunt part of his axe, he gazed at The Pencil Tree and Elder Tree wood, all glazed with globs of glistening ghee.

Let them draw their own conclusion

“What do I do now?” he asked The Pencil Tree.

“Take me to the pencil miller and have him make us all into pencils.”

“But why?” asked the woodsman.

“Because then we shall find our way into the hands of children and they will feel our spirit from centuries ago and all that we have lived and seen and heard. They will feel that spirit as they hold the wooden pencil in their hand. And then they will tell the story with their drawings.”

“But what story will the children tell with their drawings? Will they draw the story of hope and promise – of when there was a plentitude of vegetation and a multitude of animals and birds in the forest? Or, will they draw the story of destruction and deforestation and utter depletion?”

The Pencil Tree thought about the woodsman’s question for a long time and then responded:

“Let them draw their own conclusion.”

Editor’s Note

Kandhava Forest is the ancient forest referred to in the epic of Classical Sanskrit mythology, the Mahabharata. It is located west of the Yamuna River in the region of modern Dehli.

In the Kandhava Forest myth, the Lord of Fire, Agni is a twin of the Lord of Water, Indra.

The dynamic extremes of fire and water leading to destruction – as with slash and burn agriculture, deforestation, tsunamis and monsoons – reflect the unrestrained extremity of human or Mother Nature. The nurturing and life-supporting proportions of fire and water – as with cooking a meal on a fire stove, quenching your thirst from spring water – represent the gentle and divine natures. Destruction and creativity co-exist as the counterpoints of Cosmos.

by Karim